I mean, photography is all right...

… but that’s not what it’s like to live in the world (David Hockney).

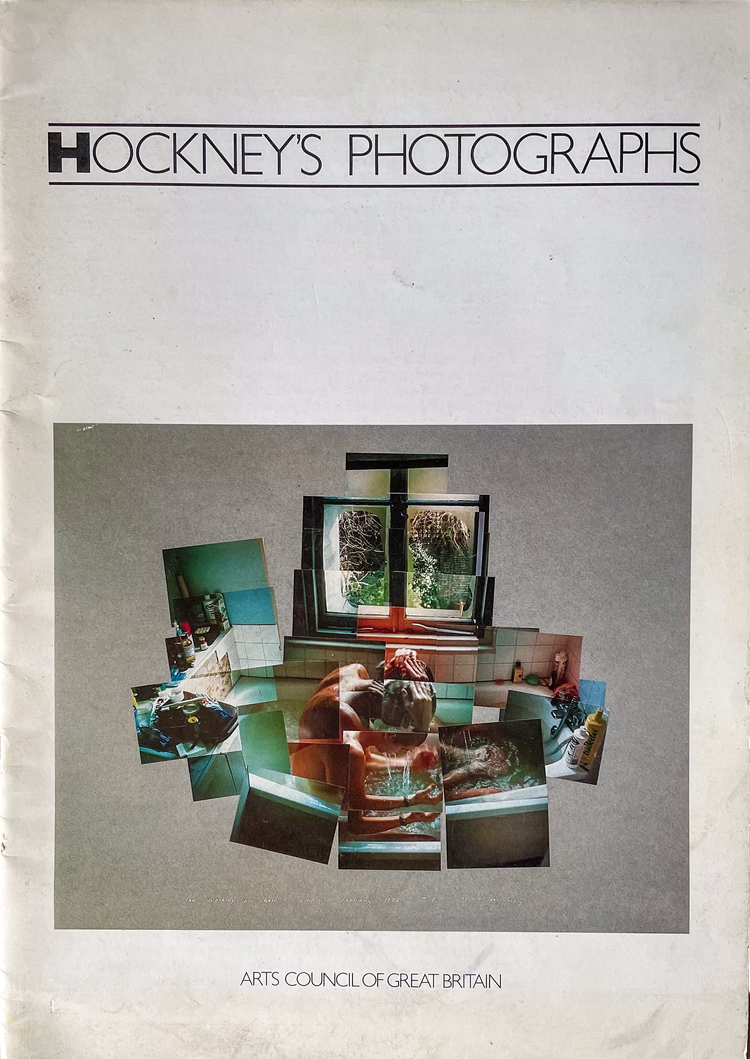

This well-worn catalogue of Hockney’s Photographs was purchased at the first exhibition I went to independently (at the much missed Royal Photographic Society on Milsom Street in Bath).

I was a callow 16 year old, in the summer after my ‘O’ Levels, on holiday in Bath with my best friend Pete.

It was one of the most formative weeks of my life. Not only did Hockney’s exhibition resonate deeply, but it was also the first time I walked round Bristol and Bath. I was so drawn to the West Country that two years later I went to university in Bristol and have lived in or near Bath for all but four years since I graduated.

Now each time I see one of David Hockney’s Polaroids, or ‘Joiners’, I recall how a switch in my brain flicked on all those years ago.

Here was a new way of seeing. A point of view which was so original to my young eyes.

Photography could be so much more than a snapshot.

“I mean, photography is all right if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralysed Cyclops - for a split second.

But that’s not what it’s like to live in the world.”

This is the challenge which confronted David Hockney in the early 80s. He felt photography excluded more than it revealed.

That a single click of the shutter was an unnatural, one dimensional way of seeing.

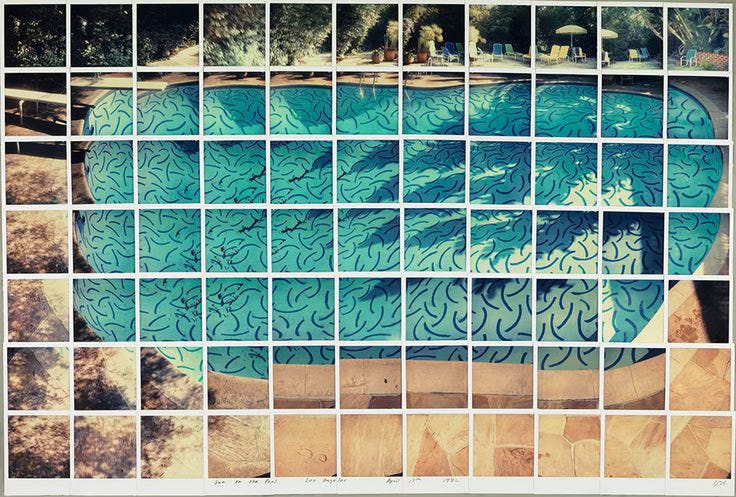

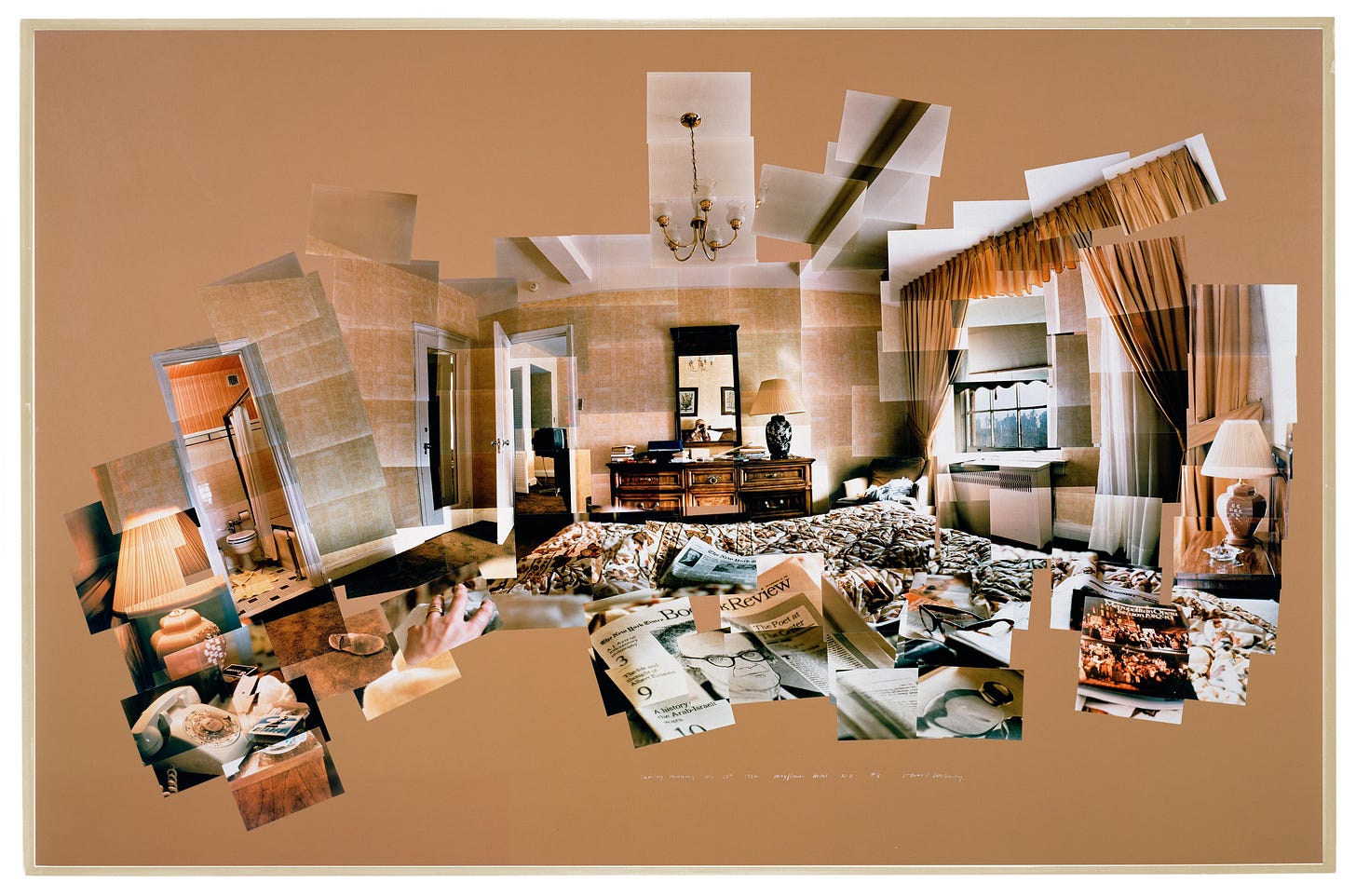

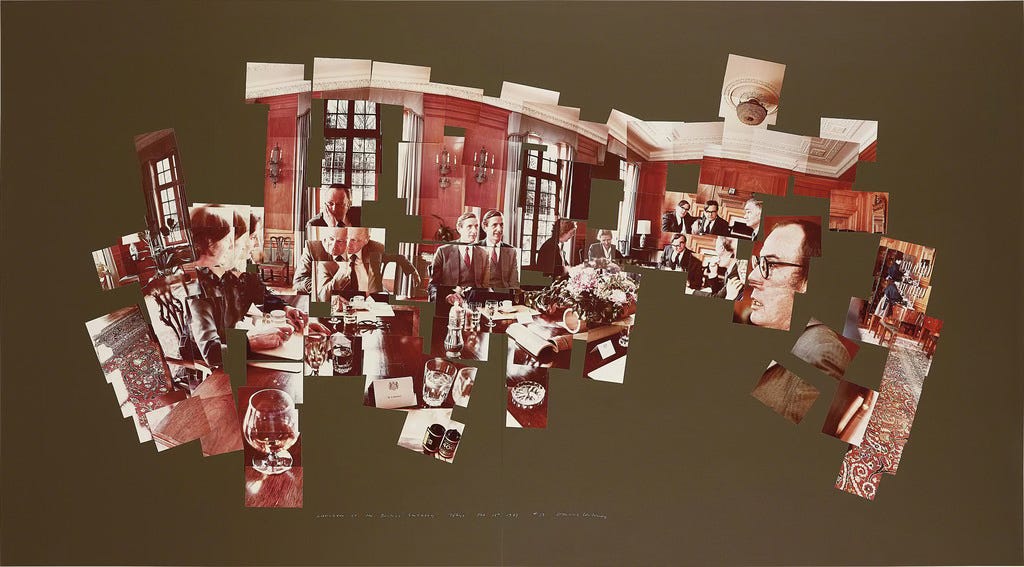

His experiments with Polaroids and then 35mm film1 offered an answer. By photographing multiple frames from slightly different viewpoints he could mimic the fluctuating glances that make up our vision. Similar in concept to Cubist art2 .

He called his collages “drawing with the camera.”

What could have been one click of a shutter is broken down into hundreds of micro-scenes. Every frame is a millisecond which combine to add layers of time. Each with a different perspective and light.

The white borders of the Polaroid and the edges of the 35mm print delineate a small portion of the scene and encourages you to dwell on each part one by one.

The scenes he chooses reflect his day to day living. The inside of a hotel room, watching Gregory swim, a car steering wheel and spending time with friends.

But by the simple act of creating a collage of related photos, Hockney manages to change the way we look at a photograph.

His works in his own words

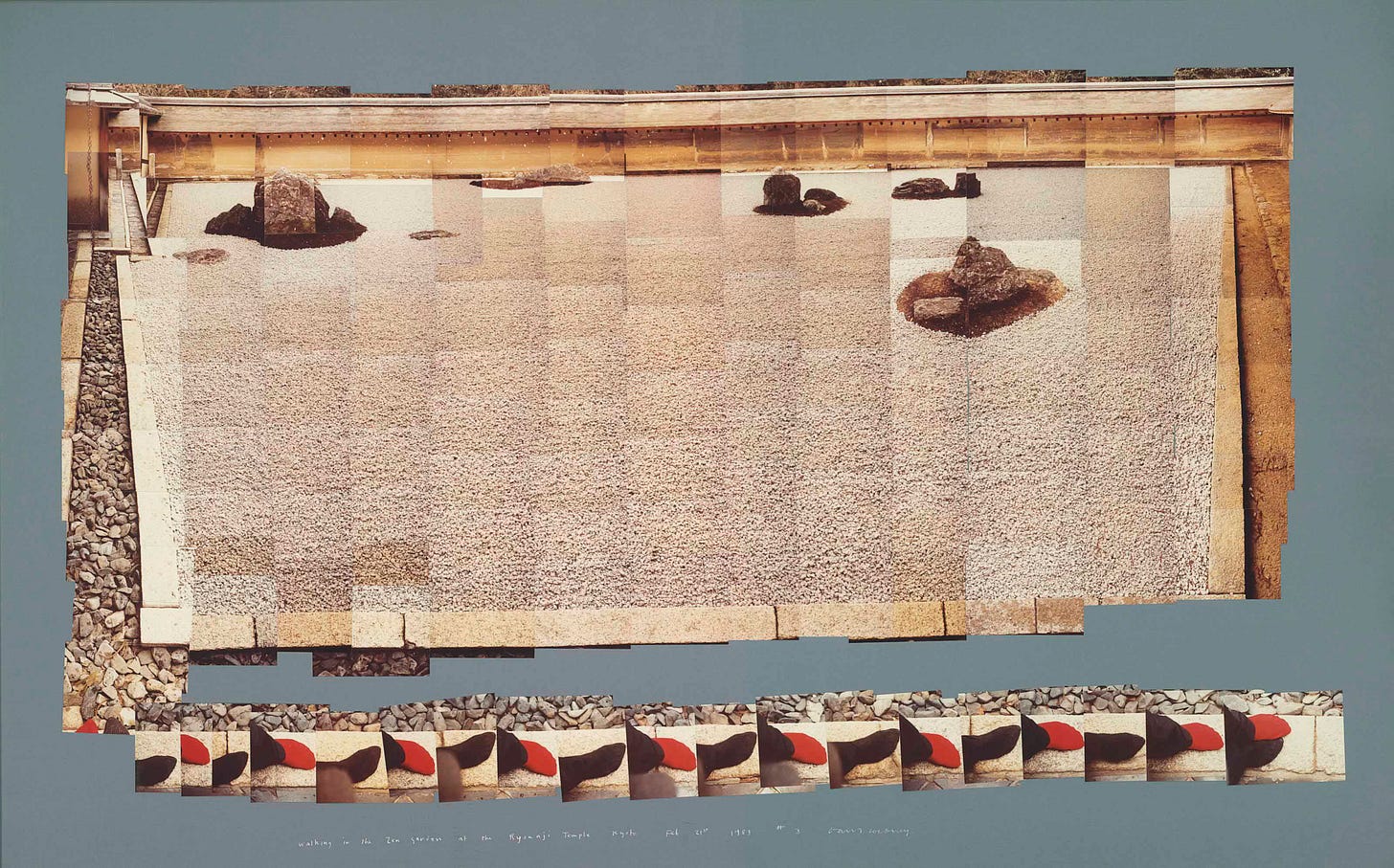

Walking in the Zen Garden at Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto. February 1983

“They said perspective was built into the camera. But my experiments showed that when you put two or three photographs together, you can alter perspective. The first picture I made where I felt I had done that was in Japan where I photographed Walking in the Zen Garden at the Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 1983. I made it into a rectangle by moving around myself and taking shots from different positions, whereas any other photograph would show it as a triangle.... I was very excited when I did that. I felt I made a photograph without Western perspective.”

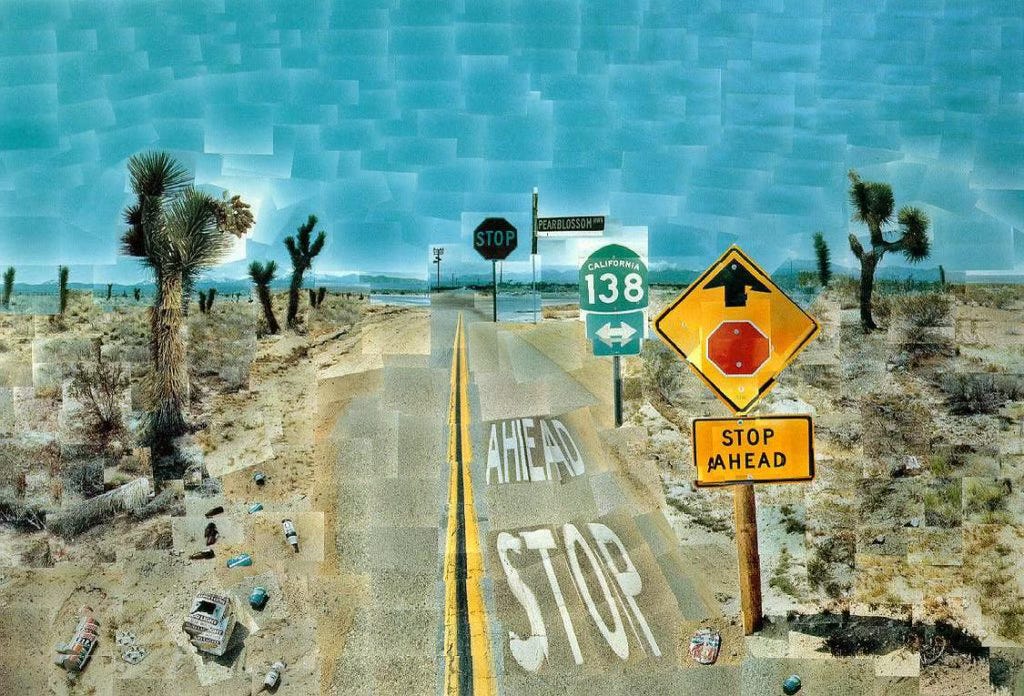

Pearblossom Hwy, 11-18 April 1986

This composite took him a week to shoot. He used hundreds of photos. The frame in the centre is the one conventional picture - the highway disappearing into the distance.

“It is the only picture that attempts to depict space, every other picture is about a surface - road signs, the road itself, shrubs, Joshua trees, and garbage at the side of the road.”

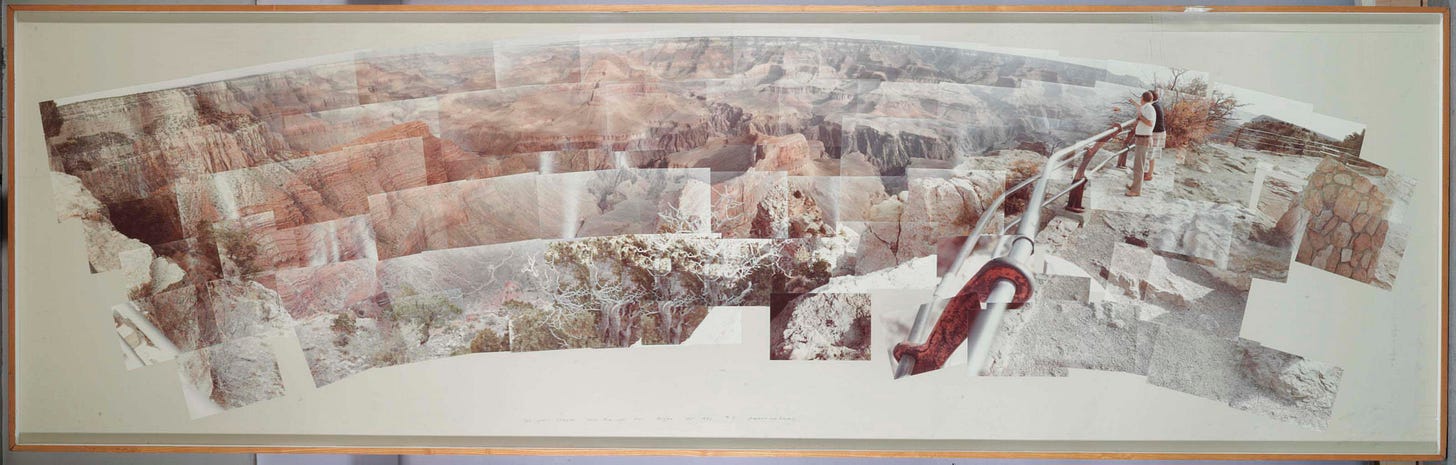

The Grand Canyon Looking North, September 1982

“I’ve always loved the wide-open spaces of the American West. But I was never able to capture them in photography, to convey the sense of what it's actually like to be there, facing that expanse - that incredible sense of spaciousness, which is somehow as elusive to ordinary photography as time is.”3

Hockney used an every day compact camera (firstly a Polaroid SX70 and then a Pentax 110), and a high street chemist to process the films.

Hockney said, “I believe that only an artist's approach will extend photography as a medium .... The Cubists were deeply involved in depicting reality more accurately than had been previously done, and I think they did in fact succeed. It seems strange that photography was not influenced by Cubism.”

Words sourced from the Hockney Foundation which provides a rich and fascinating insight into his work.

Fascinating. I was obsessed by Hockney's photo montages at the same sort of time of my life that you were (I would have been starting a two-year BTEC at Bournville School of Art!). I loved them so much that I really didn't care one jot for his painting and drawing work at the time! I adored them, but confess to not really thinking so much about what he was trying to do with them.

Proof further that our favourite photos change over time (and our memories fail to remember past favourites) as I would possibly have slipped one of these into my Desert Island Choices with @twophotographers a couple of weeks ago. Indeed, @joannamaclennan, maybe you visited the same exhibition in Bath all those years ago...?

I really enjoyed this one. Thank you for sharing! I am leaving extremely inspired to consider a new perspective and delivery with my photography.